Cyprus

a poem

My father didn’t forget the smell of tomato vines in the early morning sun, as his Dede showed him how to water the patch. In that hour before school, cycling to the bandabuliya to buy the helva for breakfast, he did not know that the hands which held his around the mouth of the hose would soon be gripping papers at passport control. Efe, the village big man, meek of his own frame jostled by nervous bodies seeking asylum. My father didn’t forget how he cried, back from school. But how could Efe (who made a cow disappear overnight and a whole village fear his vengeance) have told his grandson, ‘be brave’(?) when it turned out Teshkilat was just a word for villagers arming themselves in defence, and Enosis was bigger than all their big men. My father didn’t forget how they collected shells in their garden and played dodge the bullet or you’re dead. Nor the first corpse he ever saw in the cyan shadows of a neighbour’s corridor, squinting through the door ajar on sun-bleached street, as they burial-bathed the body without ululations. My father didn’t forget a time when there was nothing yet more frightening than the crazy twins in the walled house and a lashing from his father. And of not knowing what an irreplaceable thing is an okka of their village helva in bide still warm from the morning-fired fırın down the street. My father didn’t forget an air-raid night at the hammam which the widow ran; mothers and children sleeping side by side on the tiled floor, dependant on the kindness of Efe’s paramour. And then trying to be the eldest, on the long drive to Nicosia, in the back of a Red Cross van. Aid workers scrambling to pacify the daughter of Efe, with venom for border control guards from Greece and little fear for the baby (of name and birth month mis-recorded at the civil registry office across a warzone.) ‘Go back to your country!’ she railed. Lucky she was quite fetching, and her ‘low’ Greek (perfectly intelligible to her Urum neighbours, thank you very much) was all Greek to them. Then came England which gave with a spoon what it took with a ladle; and people told them, ‘go back to your country.’ My father learned to speak twice. And he’s sitting now on a low wall at the Valley of the Kings, telling of how they chased buzzards here as boys and vandalised ancient mosaics, to the sound of the sea churning. And he’s bearing well the indignity of their home turned into a resort for British pensioners, and settlers from a country they call ‘Israel’ so it doesn’t sound stolen. And to everyone who asks where he’s from, My father says, ‘right here. Paphos,’ pointing at the distant hilltop where a house still is, which Efe built. A decade ago, my Gran (Allah rest her) knocked on its door, and a stranger invited her in to sit in her kitchen. He was from Famagusta, he said. In the time it took to sip a findjan of (Turkish) coffee to its dregs, did she bury in her heart his story (next to all those things we cannot solve) and entrust the whole thing to God? But my father didn’t forget the smell of those tomato vines, nor the helva, unlike any other, for the rest of his life after.

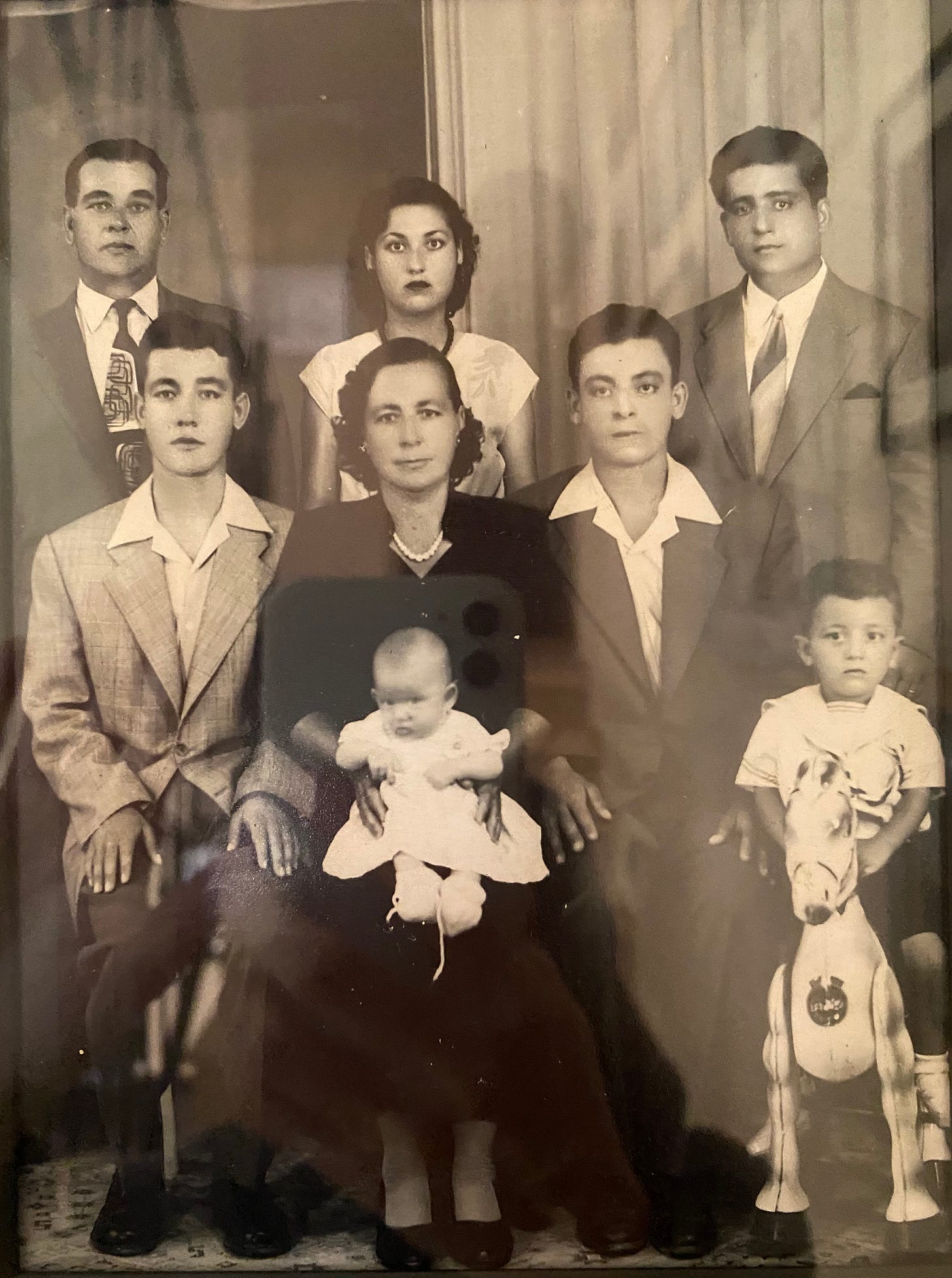

This was a lot. Wow. So much family history. How sad is it that so many can relate to your father's experiences. My own gramma had to flee Burma with my dad and some nearly 10 children at that time (she had 14 in total), all alone while my grandad tried to wrap up things and followed soon after. Fortunately for them, they actually got to go back home to India.

A STUNNING poem mashallah, dripping with remembrance. Mabrouk!